http://offroadersblog.com/wp-json/wp/v2/ By Robert Johnston @robertj55

If one position unites the spectrum of opinion of the Liberal Democrats it is the need for a proportional representation election system with a special focus on the House of Commons. There are wider considerations for electoral reform; ranging across the House of Lords, devolved government to the tiers of local government but this article will concentrate on electoral reform of the House of Commons and the attempt to achieve it in the 2010-15 coalition government.

This review is structured as follows. Firstly it covers the position of the Party going into the general election of 2010. It then outlines the negotiating of the Coalition agreement with a focus on the main electoral reform issue. The 2011 referendum campaign and the plebiscite itself are then analysed. We end with a discussion of the aftermath and options for the future of electoral reform policy.

The 2010 Manifesto

The Liberal Democrats went into the 2010 election with a clear and specific position on electoral reform. The 2010 manifesto promised to:

“Change politics and abolish safe seats by introducing a fair, more proportional voting system for MPs. Our preferred Single Transferable Vote system gives people the choice between candidates as well as parties. Under the new system, we will be able to reduce the number of MPs by 150.”

So, here was a clear statement of preference for Single Transferable Vote (STV) with an additional aspiration to reduce the number of MPs. If you are not familiar with the technicalities then a comparison of voting systems is provided by the Electoral Reform Society (ERS) who, it is fair to warn, are strong advocates for STV.

In 2010 the Party was demanding a “Fairer Britain” and electoral reform was presented as a key element of this, with the current plurality voting rule, commonly known as “first past the post”, the unfair option to be replaced. There are however diverse views on what is fair or more fair and this played an important role in the fate of electoral reform in the referendum.

Negotiating the coalition agreement

The 2010 general election resulted in a hung parliament. This left a number of possible outcomes. The most likely configuration to succeed would need to involve the Liberal Democrats; in those times the third largest party in the Commons. At the start of the process this could have taken the form of a coalition or confidence and supply arrangement with either the Conservatives or Labour. The complete story of how this developed is told, from a relatively objective Liberal Democrat point of view, by David Laws in 22 Days in May: The Birth of the Lib Dem-Conservative Coalition.

On entering a coalition it was inevitable that not only compromises would need to be made but also, as junior partner, acquiescence to measures that directly contradicted the Liberal Democrat election manifesto. These considerations and the inevitable electorate reaction were subjected to intense discussion within the party as described in Nick Clegg’s “Politics”, 2016. The resistance to electoral change by the Conservatives was, of course, well known. This was made clear prior to the election by George Osborne, but equally the commitment of the Liberal Democrats to electoral reform and it being a condition for cooperation had also been stated emphatically (Laws, 2010). The question whether the negotiation could lead to genuine proportional representation or would something weaker result needed to be addressed. In fact, the party decided early in the negotiations, when a deal with Labour was still a possibility, to press for a preferential voting system known as the ‘Alternative Vote’ (AV) rather than STV (Laws 2010 and 2016). Comparing the voting mechanisms, it is clear that the AV is essentially a special (some would say degenerate) case of STV for one seat per constituency. Under AV, if no candidate gets over 50% of ‘first preference’ votes cast, the last-place candidate is eliminated and that candidate’s second preferences are distributed to others and so on until a candidate clears the threshold of 50 percent of the vote plus one.

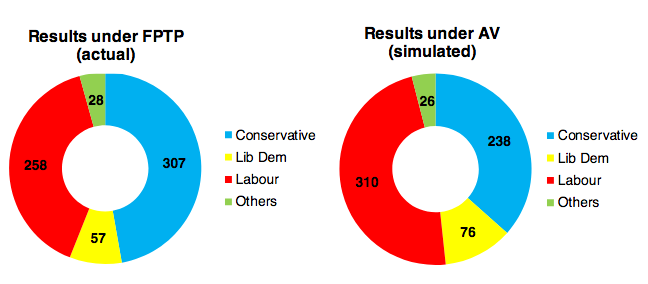

Modeling of the 2010 election shows AV in reality would have a relatively small impact on the disconnect between votes cast and seats in parliament, and would have gained the Liberal Democrats only an additional 19 seats (under a fully proportional system an additional 79 seats would be expected).

The compromise on AV was decided unilaterally by the Lib Dems in the realistic anticipation that PR, and certainly STV, would not be acceptable to the larger parties. Whether it is sensible to put forward manifesto commitments that are abandoned prior to coalition negotiations is a point we will return to later. The negotiations were robust and came close to breaking down a number of times (Laws 2010) but the Conservatives’ desire for power and Liberal Democrats’ desire for the opportunity to participate in government for the first time in many decades drove negations towards an agreement.

By the time the Coalition Agreement was issued a compromise had been reached for the Alternative Vote (AV) mechanism, with the decision on its adoption to be put to the electorate in a referendum. Although the coalition agreement committed both parties in the government to “whip” their Parliamentary parties in both the House of Commons and House of Lords to support the legislation passed to hold a referendum on AV, there was no commitment from the Conservatives to campaign for a “Yes”.

Not the result Liberal Democrat members would have hoped, but nonetheless given that AV is technically a special case of STV a two phased reform could still be hoped for with first AV followed by a move to multi-member constituencies and then STV providing a strong element of PR. This was clearly not a path that the Conservatives wished to facilitate.

The referendum on electoral reform

The campaign was fought from early 2011 and the referendum held on the 5th of May. This has been covered in detail and so only the salient points that hold lessons for the party will be reviewed and addressed here.

Based on the coalition agreement, the referendum was on a question to be decided by a simple majority:

At present, the UK uses the “first past the post” system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the “alternative vote” system be used instead?

It would be so much more straightforward and rational if the wide referendum debate was held in a spirit of informed discussion. However this, unsurprisingly, was not be.

The electoral reaction against the party’s participation in the coalition had started and, as David Laws recalled: “The No campaign had decided that their trump cards were ‘the three Cs’ – cost, complexity and Clegg.” (Laws 2016). The third of the three Cs resulted in a particularly personal bruising experience for the Deputy Prime Minister (Clegg 2016).

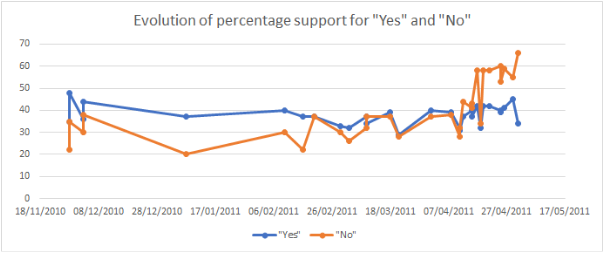

On a turnout of 42.2 per cent, 68 per cent voted “No” and 32 percent voted “Yes”. From this two points are clear; the electorate was not highly motivated and those who cared enough to vote chose “No”. However, public opinion started out being quite positive for “Yes”. Polls from six months before the referendum show several months of solid support for “Yes over “No” (but with a percentage of don’t know or undecided at about 40%).

What the data show is that while the percentage support stayed steady at about 40%, the undecideds ended up with the “No” camp. This indicates that the “Yes” campaign was relatively ineffective.

Although the numbers indicate that the “No” campaign was more effective it has come in for sharp criticism even from the Conservative side with Michael Portillo writing in the Financial Times, “During the referendum campaign, the Prime Minister forgot the importance of courtesy towards his political partner … in a moment of weakness he linked himself to the disgraceful “No” campaign making life extremely difficult for his deputy.” Although the “No” campaign was fought in terms that disadvantaged the Liberal Democrats, the party needs to learn from this and be realistic about the tactics that will be employed when attempting electoral reform. On a more principled level the “Yes” campaign needed to address and respond to other views on electoral fairness. The “Yes” campaign was also disadvantaged by it being common knowledge that the Liberal Democrats were not strong advocates of AV.

The referendum defeat was a major setback for electoral reform of the Commons and strained the Coalition to breaking point (Clegg 2016). Now, eight years later, is there much hope for electoral reform in the near future?

The aftermath

The immediate reaction in 2011 to the referendum result was to try and recover by pushing other aspects of political reform such as election of members of the House of Lords. Eight years have now passed and a lot has happened to shake confidence in the solid, pragmatic way of doing things in the UK. The opportunity for electoral reform and wider constitutional debate could well arise from the current chaos. The Party must be prepared for this and be realistic about all the ramifications and views involved. In this context it is important to realise that all voting schemes have their strengths and weaknesses. There are even theorems in social choice theory proving that any scheme must be flawed. There are a diversity of views on what constitutes fairness and different voting schemes cater to those views. If an election is framed as a race, then for many people “first past the post” will seem quite fair.

What this discussion is leading towards is the need to manage expectations of what can be achieved merely through adopting one voting rule rather than another and go further with wider constitutional reform. Even when there is strong consensus, as there is in the Liberal Democrats, it is useful to critically evaluate a position in terms of principle and detail. Then, even if the position does not change it is strengthened through being subjected to the review.

The party has concentrated on the fairness of proportionality as reflecting the choice of the electorate but we also need to introduce other positive aspects of the scheme that we put forward. STV is a system that facilitates the growth and representation of a diverse number of groupings that can formulate, criticise and propose solutions to the challenges faced in society. This gets away from the criticism that the Party’s proposal is merely self serving just as the position of other major parties is for the status quo. Importantly, whatever the ideal position is, the party must adopt manifesto commitments that a realistic and realisable

We must widen the criticism and present the purported strength of the plurality voting (first past the post) rule, that it tends to lead to two major party blocks, as a source of weakness rather than strength. In the plurality system other sources of ideas and opinion can be safely ignored by these two major blocks. What tends to happen under plurality voting is that the major parties tend to absorb the more extreme positions, as can be seen clearly in the current situation in the UK where the Conservatives contain a substantial and influential group of English nationalists, and currently the Marxist faction leads the Labour party. So, there is diversity but it is an internal management issue for the main parties not a constructive component of the national debate. Smaller parties are traditionally ignored except when there are small majorities or hung parliaments.

So, it may be clear that plurality voting rules should go, but this still leaves a number of methods in addition and in contrast to PR and there are also numerous flavours of PR. All this needs to be engaged with. For example, it is easy to see that Condorcet methods will also tend to correct for deviation from the popular vote but whether these methods provide for and nurture diversity of opinion awaits further analysis. In a social choice setting the fairness encapsulated in the Condorcet mechanism is defendable as is the proportionality notion. Generally, looking beyond the election of MPs, consideration should be given in a case by case basis as to which is the appropriate voting rule; whether in general elections, internal voting in Parliament and other bodies, and at different levels of government.

As things stand, not only theory but the evidence shows PR to hold an advantage in the creation of a diverse, multi-party public sphere, which together with the right institutions would provide a robust foundation for an open society. For a well functioning constitutional democracy it is the suppression of diversity of opinion that is the damning consequence of the plurality voting rule. PR is much stronger in nurturing small parties and opinion groups, and giving them open representation. What is also needed in addition is reform of institutions to make sure that this diversity leads to robust debate and effective policies rather than chaos or weak compromise.

http://e17arttrail.co.uk/take-part/ If you would like to contribute to Liberal Reform’s review of the Coalition, please email robert.johnston@liberalreform.org.uk